Bagshaw’s Gridiron Grit

Editor’s Note: Originally published September 23, 2017. Republished February 4, 2021.

1914

So, you want to play high school football.

You go to the pre-season meeting at Everett High School gymnasium, sit down on the bleachers next to the other sons of millers and fishermen. Your cohorts are all on the scrawny side, maybe used to skipping meals toward the end of pay periods. With few exceptions, they look like they would be clobbered in a scrimmage.

The coach comes out, strutting around, no clipboard no whistle. His name is Bagshaw, but everyone calls him “Baggy.” He’s short, Welsh, and his favorite words are damn and hell.

He says, If you wanna play football you gotta keep your ass down and bring your own gear.

So your mom stitches together a leather hat-type thing for you. Looks like an aviator helmet, really. At a teammate’s suggestion, you buy “high shoes”, glorified walking boots that lace up to the ankles, and pay a cobbler in town to add spikes to them. Cleats.

You’re ready to play ball.

What you’re not ready for is Baggy. His intensity.

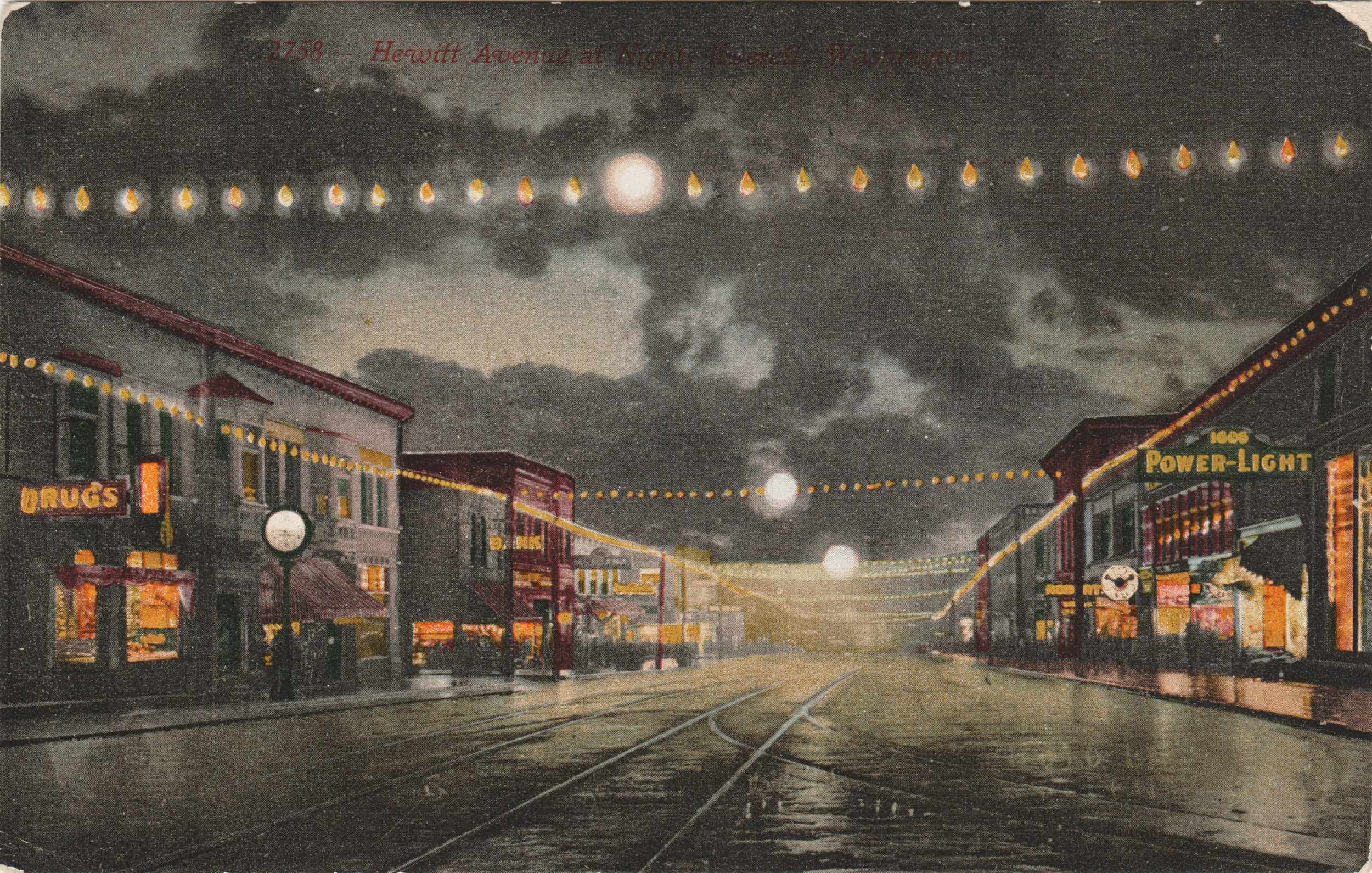

You run every day from the new school on Colby to the Seivers’ Field near Hewitt & Virginia.

You run plays until it’s dark, no pause.

Passing the pigskin. Punting. Sacking. Tackling. Pushups.

If Baggie’s in a bad mood you run after dark, between the streetlights. Then you run back up the hill to the high school.

If there are any laggers in the pack, Baggy is on them with his damns and hells, assigning them additional mileage. Pick it up, kid. No slouching. That's an extra lap, son.

While your group runs laps he’s running on the inside of the track, pacing the team and making sure no one cuts corners.

You start to hate him. Really hate him.

Most days you’re the last one up the hill so you’re the last to hit the showers. The hot water’s gone so you splash yourself with cold water on the face and limp home to take a bath.

The next day you’re exhausted and sore, dragging your way through vocational classes.

Why, Baggy. Why.

The following morning you wake up feeling stronger, better.

You feel like you have something new to bring to the next practice.

Baggy keeps churning out the wins. Your team, Everett, earns a series of victories on the field that are exhilarating on one hand but almost boring in their regularity and predictability.

You trounce the University of Washington 19 to zero. Next weekend you smash St. Martin’s 20 to zero. Wenatchee gives you some grief: they have a fullback named Hippo. He looks like a slab of beef stuffed into football pants. You pull out the win, but your shoulder aches from sacking Hippo time and again.

Football is a game of endurance. There are no face guards. There are no pads. Substitutions are rare in 1913—if you pull a fella you have to wait until the next quarter to sub him back in. So Baggy makes most of the kids play through their injuries.

The game becomes a contest of pummeling. Broken ankles and concussions happen regularly.

All of that training is paying off: Everett are the chief pummellers in the region. Seattle high schools don’t want to play Everett anymore. They say they have enough schools to start their own league next season.

Everyone knows what that means.

Babies. Pantywaists.

That season Baggy leads your Everett High School team to victory, securing the title of Northwest Champs in the playoffs in Long Beach, California. Coach insists in bringing down barrels full of Everett drinking water to the playoffs, not trusting the quality of California water. Only the best for his players.

Back home, Everett is your oyster.

Everyone knows you’re on the championship team. People nod as you ride the Colby trolly to the Dolson & Cleaver dry goods store. Mr. Cleaver puts an extra spruce beer on the counter when he rings you up—this one’s on the house.

You graduate vocational school, work the mills. You build your own home in the wooded Riverside neighborhood, a small bungalow mail ordered from a Sears catalog. Make house payments on installments. Attend a nice Lutheran church.

You keep going, advancing, making promotions. Any time you feel your stamina flagging from long hours at the mill or the grueling task of hacking it in a rough-and-tumble smokestack city you hear a small voice in your ear.

The voice has a Welsh accent and it’s saying dammit to hell, son. Pick it up, kid. No slouching. You got this.

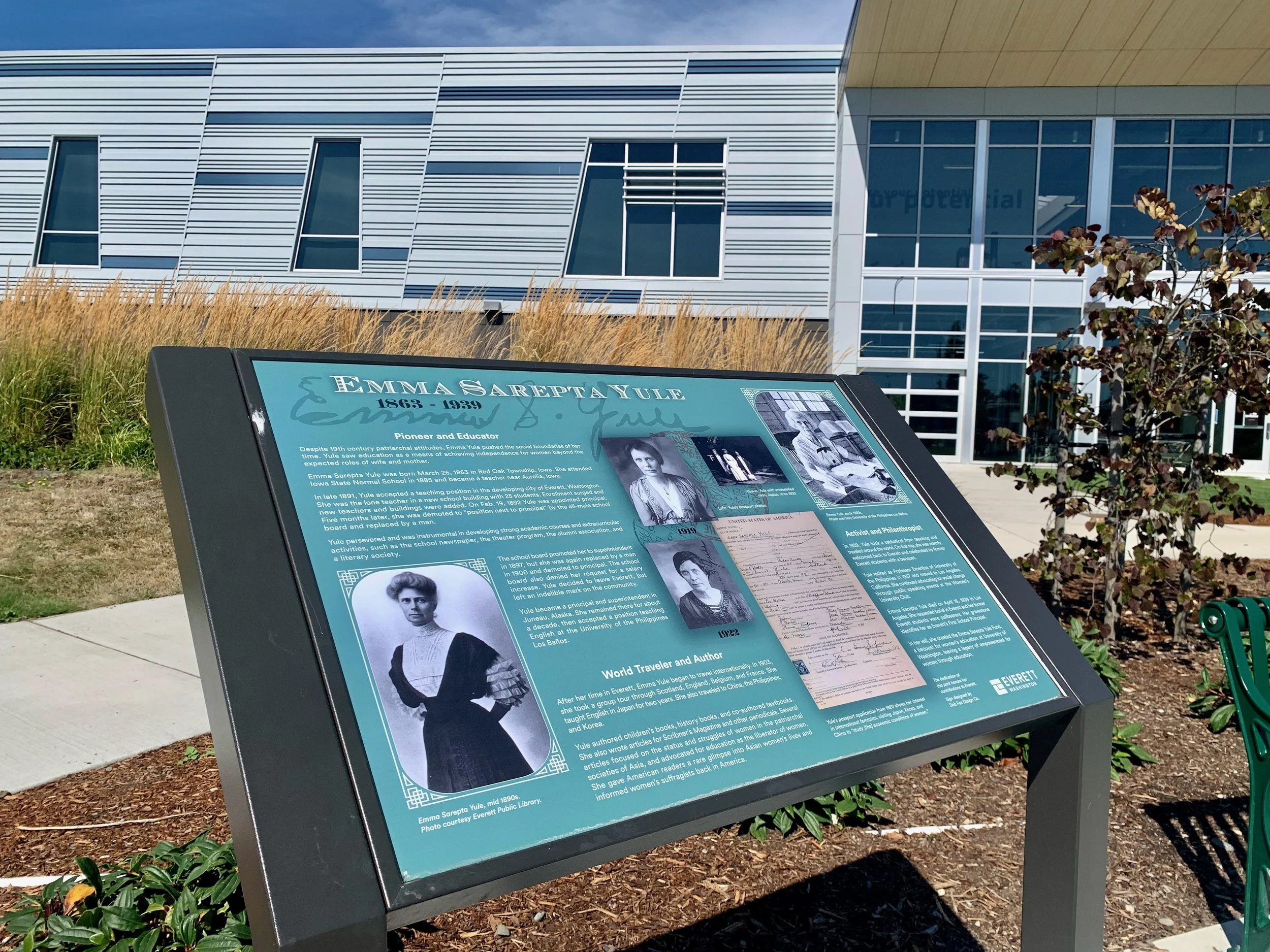

Enoch Bagshaw (back row, far left) was a championship football coach, first for Everett High School athletics, then for the University of Washington. He died in 1930 at age 48.

Bagshaw Field is located at 2400 Rainier Avenue and is named in his honor.

Richard Porter is a writer for Live in Everett. He lives here and drinks coffee.